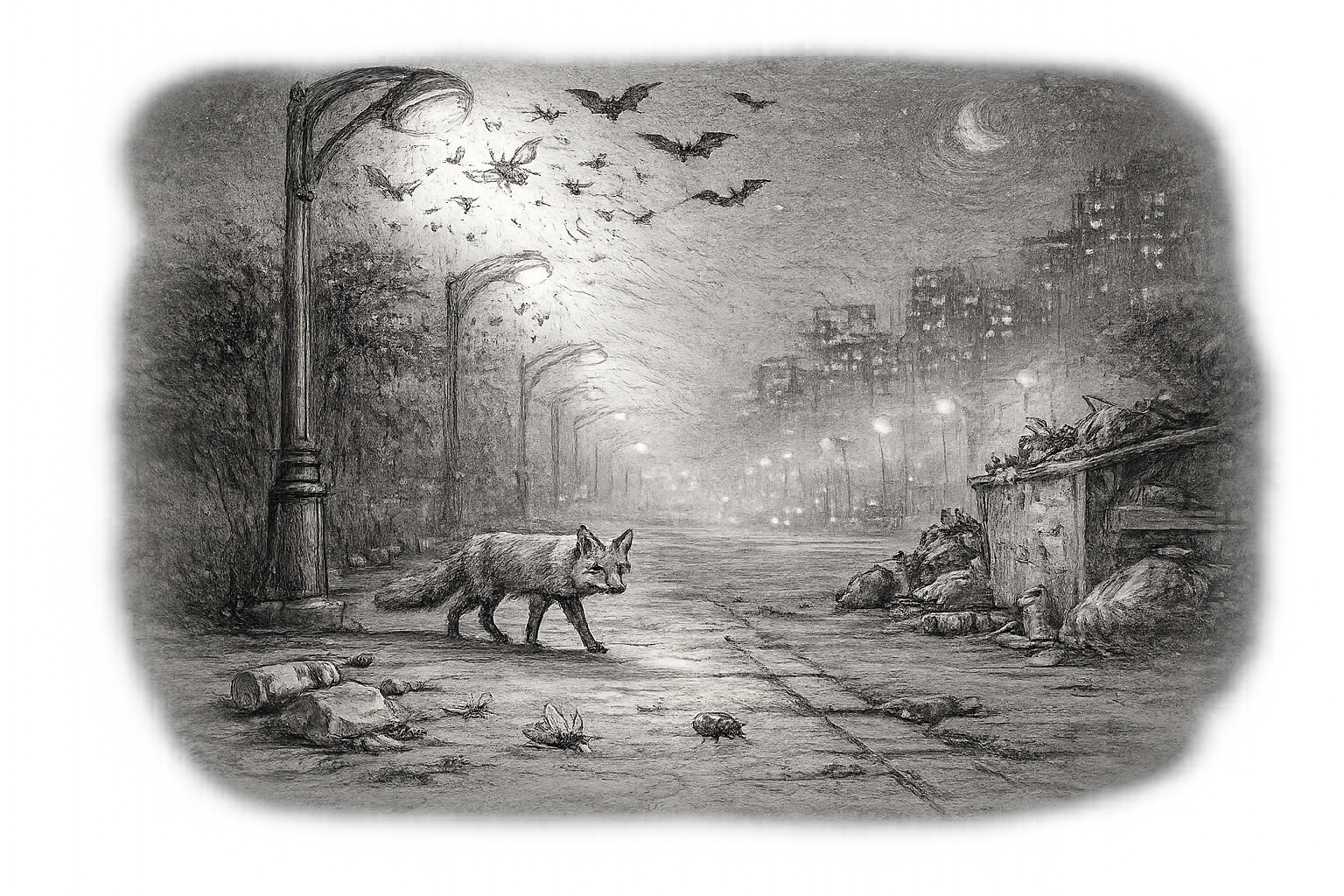

A chronicle of a nighttime walk (and what everyone can do about light pollution)

There is a very precise moment when the day withdraws. Not a spectacular second, more of a slide. The air cools, colors dim softly, silhouettes simplify. The last blackbirds finish their phrases; the crows fall silent. You expect night to take over, with its own texture, rarer sounds, greater distances.

And then, in many places, night never quite arrives.

That evening, I’m walking with no particular destination. A simple loop: a few streets, a stretch of path, a park, then back home. At the hour when dusk should lay down a deeper silence, the city comes back on like a theater set. Streetlights, shop windows, signs, façade floodlights, parking lots. A crisp, efficient white light, we tell ourselves. And above all, everywhere.

I stop under a streetlamp.

In the halo, the air is alive… but with a trapped kind of life. Insects spiral stubbornly, as if magnetized. Some collide and fall; others drop, take off again, return, and return. Immense energy spent for nothing. On the ground, a few tiny bodies already still, unseen by anyone who doesn’t look closely. It seems like a small detail. And yet it’s a key scene: here, night is no longer a habitat. It’s a trap.

What strikes you is the imbalance. A single point of light is enough to rewrite the behavior of dozens (sometimes hundreds) of living beings. Light doesn’t only illuminate: it attracts, repels, disorients, fragments. It redraws the map of movement. It imposes a rhythm. It shifts the balance of power.

Nocturnal biodiversity exists everywhere, even in cities. It is simply more discreet, more fragile, more dependent on darkness. And darkness is precisely what is becoming rare.

Night is a habitat (not a “void”)

We often talk about nature in terms of species and environments: forest, river, meadow. We forget a cross-cutting parameter, as decisive as water or temperature: light.

Night is not the absence of day. It is an ecological condition—an environment in its own right. Some species hunt in it; others move through it, reproduce, rest. Night is a breathing space for ecosystems, a time when relationships change: prey emerge, predators become active, nocturnal pollinators work, temperatures drop, humidity rises.

When we light continuously, we are not “adding a bit of comfort.” We are changing the rules of the game.

What light disrupts, concretely

Without turning this into a lecture, here is what is observed very simply:

Disorientation of insects: many species use the moon and celestial cues to navigate. A streetlamp becomes a false star that attracts and traps.

-

Energy depletion: circling a light source is exhausting. For an insect, that lost energy can be the difference between survival and death.

-

Easier predation: halos create artificial hunting zones. Some predators adapt to them; others avoid them. The balance shifts.

-

Disturbance for bats: some avoid lit areas (they are more vulnerable there); others concentrate around streetlamps where insects gather. Either way, “natural” night becomes fragmented.

-

Bird migration and orientation: powerful lights (especially during migration and under overcast conditions) can disrupt trajectories.

-

Biological rhythms: artificial light influences cycles (activity, reproduction) across many groups.

-

Plants and insects: by changing nighttime rhythms, we indirectly affect pollination, food webs, and resource availability.

None of this is abstract. It happens at the scale of a streetlamp, a parking lot, a façade, where we live.

First principle: light better rather than more

In the field, the same objection comes up: “We light for safety.” That’s legitimate. But the solution is not necessarily “more.” It is often “better.”

Useful lighting is:

-

aimed at the ground (not toward the sky, not horizontally),

-

limited in time (when it is needed),

-

limited in intensity (the right level),

-

warmer in tone (less harsh, less dispersive).

This is not a return to candlelight. It is intelligent adjustment.

And that is where the practical begins: everyone can act, at home first, then beyond.

1) Act immediately: at home (house, garden, balcony)

The most effective action is often the simplest: switch off what does not need to be on.

Reduce duration

-

Turn off outdoor lights as soon as they are no longer useful.

-

Program an automatic shut-off (timer) or use a motion sensor to light only when someone passes.

-

Avoid decorative lights left on all night.

Aim properly

-

Install fixtures with shades, directed downward.

-

Remove spotlights that illuminate trees, façades, or the sky (they create large, useless halos).

Lower intensity

-

An entrance does not need stadium lighting.

-

When possible: reduce wattage, choose weaker bulbs, or use several small downward points rather than one floodlight.

Choose a softer light

-

Favor a warm tone and avoid very white light, which disperses more.

-

Visual comfort is often better, for us, too.

Result: less halo, fewer insects trapped, less nighttime fragmentation, and an immediate gain in energy sobriety.

2) Act without conflict: propose a trial in a co-owned building

Co-owned buildings are an underestimated lever. Many “too much” lighting setups come from a collective decision never revisited: an old setting, a fear, an implicit norm (“we’ve always done it this way”).

The most effective strategy is rarely confrontation. It’s experimentation.

A simple proposal (easy to accept)

-

Partial shut-off during a calm time window (for example, the heart of the night).

-

Motion sensors in passage areas.

-

Re-aiming fixtures that light the sky or shine into windows.

A short argument set

-

Safety: keep light where it is truly useful (paths, doors), and avoid over-lighting that creates strong shadow contrasts.

-

Comfort: fewer nuisances for residents (light in bedrooms, visual fatigue).

-

Energy: a direct reduction in consumption.

-

Biodiversity: restoring a minimal “night” beneficial for insects and bats.

A simple multi-week test, with feedback, is often enough to unlock fixed situations.

3) Act where it matters: in your neighborhood and with your municipality

At the territorial scale, the decisions that truly count are often municipal: street lighting, parks, façades, business zones.

Good news: many municipalities are already changing their practices, sometimes for energy-saving reasons, sometimes for biodiversity, often for both. A clear citizen request helps.

What you can do concretely

-

Ask whether a nighttime switch-off plan exists and which neighborhoods are concerned.

-

Report clearly excessive lighting (floodlights aimed at the sky, deserted zones overlit, poorly oriented fixtures).

-

Propose a win-win approach: security on sensitive areas, switch-off elsewhere, sensors, lower intensity.

One simple idea to share

Biodiversity isn’t protected only in reserves. It is also protected through ecological connectivity. Night has its own connectivity too: dark corridors, quiet zones. Creating “darkness networks” reconnects nocturnal habitats.

4) Act in business: parking lots, signs, façades (big impact, simple moves)

In professional settings, lighting is often automatic: parking lots lit all night, illuminated signs with no real utility, façades “showcased” continuously.

Yet this is an extremely concrete action reservoir.

5 simple, high-impact actions

-

Schedule shutdown of signs and façades outside operating hours.

-

Use sensors in passage areas rather than constant lighting.

-

Re-aim fixtures toward the ground (remove beams toward the sky).

-

Reduce power when the site is closed.

-

Zone lighting: illuminate only where it is necessary.

Why it’s strategic

-

Direct savings.

-

Reduced nuisance for nearby residents.

-

A credible CSR action (visible, measurable, non-cosmetic).

-

A real contribution to local biodiversity.

-

And it is easy to rally people internally because the difference is immediate.

False good ideas (and why they miss the target)

Certain “solutions” come up often. They feel reassuring, but they are ineffective, or even counterproductive.

-

“We’ll light more strongly to be safe.”

More power = more halo, more glare, and stronger shadow zones. Safety comes from designed lighting, not maximum lighting. -

“White light helps us see better.”

Sometimes you see “sharper,” but you also light farther and more diffusely. A warm, directed light is often more comfortable and more sober. -

“Decorative spotlights look nice.”

Nice, yes, but if they’re on all night, they turn the neighborhood into a permanent film set and remove refuge zones.

The point is not to ban everything. The point is to choose: where, when, how much, and for what.

A very simple checklist: “My lighting in 10 minutes”

If you want immediate action with no major work:

-

Does this light need to be on all night?

-

Can I put it on a timer or sensor?

-

Does it light the sky or a tree unnecessarily?

-

Is it too powerful for the need?

-

Can it be aimed downwards?

-

Is its color very white?

-

Does it bother neighbors (windows, bedrooms)?

-

Is there a dark “refuge” zone at my place (even small)?

-

Can I remove one light point without losing comfort?

-

What action do I take tonight, concretely?

The end of the walk: a night a little more alive

I continue. Farther on, one street is less lit than the others. Not dark. Not unsettling. Just softer. It’s surprising how quickly the eye adapts. How much easier you breathe. How space becomes wide again.

In that zone, you see again what you had forgotten: shadows, depth, the sky. And sometimes a discreet detail (a quick flight, a brush of movement, a small motion near a wall) that reminds you that night is a world of its own.

Acting concretely against light pollution often means removing rather than adding. It isn’t spectacular. It is precise. And it works.

Reducing unnecessary lighting gives biodiversity back part of its habitat and, along the way, gives our nights back some of their quality.

Comments